- Home

- Colleen Oakes

The Black Coats Page 2

The Black Coats Read online

Page 2

Where the hell am I? The map had taken Thea onto a long, wooded stretch of road. Bur oaks and cedar elms hovered over the area, their crooked arms stretched protectively through the space. Shadows passed over Thea’s face as she slowed the car. The houses there were hidden from view by private driveways—their true size tucked away, a privilege of the very wealthy. She kept going, seeing no sign of Black Locust Drive, and pulled the car over when she came to a dead end. Thea got out of the car. The road had ended at a large cypress tree, absolutely massive, its thick trunk swallowing what remained of the road. Thea unfolded the map again, trailing her finger over the twisting path that had led her there. On the map, there it was, Black Locust Drive, and yet she was standing here and there was no house, no road.

The wind picked up and the tree gave a shudder. Its ancient arms—some wider than her body—creaked in the breeze. The roots carved out a hole in the earth around the tree and created a yawning void about five feet deep. An unfriendly finger of dread was creeping its way up her spine, and Thea had the distinct feeling of being watched. She spun around, shoving the envelope and the map into her back pocket, her jeans soaked and stiff. In the tree, a black shape fluttered and caught her eye; Thea squinted to get a better look. A magpie was nestled high in the tree, its sharp beak eating some dead thing.

Thea’s heart leaped. Just over a few branches from the bird, a black envelope hung from a piece of burlap twine, curling in the wind.

Two

Dwarfed by the massive tree, Thea put her hands on her hips, knowing that she looked just like her father at the moment.

“Well, shit.”

She looked into the muddy crevasse, shuddering as a water moccasin slithered across the shallow water. This is crazy. Except, there was no turning back now. There was an answer in that envelope, or maybe in the next one, and besides, she hadn’t been this awake in months. She had forgotten what it felt like to be excited; her heart was pounding, and the gray fog in her brain was lifting. It felt good. It felt scary.

It felt different from grief.

With a wry smile, Thea remembered that she was kind of awesome at this. Last year she had been the Roosevelt High track record holder in both the 200- and 400-meter dash. That was before, of course. Thea backed up about ten feet. She paused, remembering how it felt to soar over hurdles, the momentum pitching her forward. Then Thea broke into a mad run, flying toward the tree.

When her feet hit the lip of the ditch, she hurled herself into the air. Her momentum carried her over the ditch and up to the trunk of the tree. With a sigh of relief, Thea paused for a breath, brushing off her hands on her damp jeans. Okay, she thought. I got to the tree, now how the hell to get up the tree? Jumping was useless, seeing as how the branches were at least eight feet above her.

And then it began to rain, as bouffant gray clouds churned into themselves. Thea felt a sprinkle of water brush her cheeks. “Are you serious?” she shouted at the sky. Why does so much of this adventure have to be wet? Thunder crackled above, and the wind circled angrily around her. She watched as the tree swayed, its vines blown loose from their safe havens. Thea blinked. The vines.

She ran around the trunk, not wanting to lose the momentum of the wind. The branches at the back had the most vines, thick, loopy ropes that choked the huge trunk. She leaped three times before her hand closed around one.

Rain poured down on her face as she looked up.

“You can do this.” Her voice wasn’t as confident as she would have hoped. She planted one foot on the tree and, step by slippery step, began making her way up. The rain was almost blinding at this point, but she kept moving until the lowest branch was close enough to reach. Thea cautiously reached one arm around the slick wood before pulling her legs up. The envelope was maybe only ten feet above her now. Moving as quickly as she dared, she made her way from branch to branch, her hands clutching so hard that they hurt.

She reached for a branch, almost there . . . and then the branch she was standing on broke beneath her feet. Thea lost her footing and caught herself on the branch below her with a loud crack. She gasped as the wind was knocked out of her lungs, and she struggled to hang on. Finally, she inhaled, gulping greedily as she caught her breath—and her balance. The envelope was just above her now. Thea moved up another branch and snatched it with her fingertips. She yanked open the envelope, this time not pausing to admire the rich paper.

Take the slide, then quickly make your way to the black gate.

Mademoiselle Corday waits for you.

Thea steadied herself on the branch beneath her feet, looking at the landscape below. Maybe a quarter of a mile from where the road ended, she could see a thick swath of trees swaying in the violent wind. Her breath caught in her chest. Beside the trees, a black iron weathervane shaped like a butterfly spun in the breeze.

“Oh my God,” Thea muttered. This was real. There was a house in those trees.

And she needed to get inside.

She reached down for the branch below her and stopped with a jerk. Slide. Impossible to see when looking up at the tree, but now perfectly laid out when viewed from above, the trunk of the tree gradually declined into a smooth ramp that would spit her out at the edge of the ditch. This was madness. She should be just getting out of history class right now, hating her existence. Instead, she was going to slide. Thea let go of the branch. After a second of free-falling, she felt the trunk slam hard against her back. The rain sped her descent, and in a few exhilarating seconds the tree dumped her out onto the wet ground.

She began laughing at the absurdity of it all: the envelope, the fountain, this freaking tree. She laughed until her stomach ached, probably going mad but loving every minute of it. She hadn’t laughed like that in so long. “Thank you,” she whispered. She sprinted fearlessly toward the thicket of trees, deafening cracks of thunder shaking her teeth as she raced toward whatever mystery called her forward.

Once she passed the trees, the iron gate gradually rose above her as she neared it. The swirls of pointed metal, topped by a black butterfly, stood firm against the wind. Thea was surprised when the gate swung open at her touch. She took a deep breath as she made her way through the gate and underneath a portico dotted with yellow rosebuds. Eventually, Thea stepped out into a clearing, her feet landing on smooth gravel.

“Whoa,” she murmured. She was in front of one of the largest houses she had ever seen. A formidable fortress that loomed over the fields and trees, the enormous black house towered above her—vicious, beautiful. Slanted gables dotted with gold rose above her head, each one hosting ornamental gargoyles that leered menacingly down at her. The house and its land seemed to sprawl out in all directions and looked like it was constantly being built upon; a sort of madness in its very design. From where Thea stood, she counted at least four floors above her. Just behind it, she saw a hint of a gold-tipped dome.

She pushed her wet hair out of her eyes and slowly walked toward the gigantic door. A bronze plaque greeted her: Welcome to Mademoiselle Corday.

Beneath the words was the same symbol that adorned the weathervane and the envelopes: a black butterfly.

Thea blew out a long breath. She closed her eyes. This was the last moment she could walk away. This was either going to be life-changing or life-ending. She looked up at the sky, the storm churning the clouds into a foamy green gray. Somewhere deep inside she knew that her decision had already been made for her, had been made the minute the envelope slid across her bag in pottery class. Had been made that day, on the track.

Thea, something happened to Natalie.

That was the moment when nothing would ever be the same again. That moment had made the choice for her. Now there was only moving forward. The past was without a heartbeat.

Thea reached out to lift the knocker and paused, remembering the note: Mademoiselle Corday is waiting. Instead of knocking, she pushed against the wooden door and watched it swing open. The woods behind her filled with the sound of rain as she stepped insid

e. The door slammed, the loud bang echoing through the silent house. It was pleasantly warm, but Thea shivered nonetheless, overcome by the feeling—no, the certainty—that she was being watched.

The grand foyer was empty save for an antique table that held a black envelope and a pile of clothing. Thea stepped forward, leaving puddles on the floor with each step, and unfolded the note.

Change into these clothes.

Take the stairs to the right and get through the black door.

Turn back or forever be changed.

On the table were a folded pair of leggings, a simple long-sleeved shirt, and a pair of ballet slippers. All were black.

“Please, God, don’t let me be on the internet right now,” Thea mumbled as she stripped off her soaked flannel and peeled the dirt-soaked, waterlogged jeans from her legs. Thea pulled on the leggings and slipped her feet into the black ballet slippers before folding up her dirty clothes and placing them in a plastic bag on the floor. Her soaked, heavy hair was becoming a burden, so she twisted it up into a high bun. Behind the table a long staircase gracefully climbed upward, dividing halfway and turning into separate spiraling staircases. Thea went right, taking two stairs at a time. She circled above the main floor once, again, and then once more before they led to an open door. This time, she didn’t hesitate. She walked through, ready for whatever complex obstacle lay on the other side.

Except that there was a boy on the other side.

Thea leaped back with a yelp as her heart pounded with fear. Had he brought her here? He stared down at her, unnerving in his intensity.

He stood about six feet tall, lean but muscular, maybe only a year or two older than she was. He wore loose white linen pants that dusted the tops of his veined, hard feet. His black hair was cropped close in a military fashion and stood in direct contrast to obscenely wild dark eyes. His skin was light brown, and he looked to be of Indian descent.

A nameless alarm began rising in her, a pulse that beat up through her ears. The boy stared at her, not speaking. Finally, Thea raised her voice. “Hello?”

The boy gestured to the door behind him. “Get through the door,” he said simply. Then he stepped back.

Thea nodded. “Right. Get through the door.” Taking a far step to the side, Thea moved toward the door, hoping that he was simply a kind of doorman, an ornamental finish to whatever this elaborate show was. He did not move from his position in front of the door, and the space between them didn’t allow Thea to squeeze through.

“I’m sorry, I may need you to move.” The boy stared forward, hands folded in front of his waist, body rigid and as still as a stone in a stream. He said nothing as Thea stepped cautiously in front of him. “Yeah, so . . . I’m just going to scoot through here. . . .” She tried to duck under his arm politely, but her shoulder bumped up against the cave of his ribs.

Suddenly and without warning, he threw her across the room. She felt her feet leave the ground as she slammed into the wall behind her like a rag doll. The pain was white-hot, throbbing. Thea clenched her teeth to keep from crying out as she clutched her arm protectively against her ribs. The man stepped back in front of the door without a word, his arms crossed calmly in front of him.

Thea lifted her head, staring at him with barely concealed rage. “What is wrong with you?” she spat. He didn’t answer. She slowly climbed to her feet. “Let me through the door. Please!”

The boy, who seemed more and more like a phantom with each passing moment, stood quietly. Get through the door. So it’s going to be this way. Okay. Thea sprinted toward him and slammed her shoulders against his stomach, hoping to push him back through the door with her. Instead, using her own momentum, he picked her up and spun around, roughly throwing her down on the mahogany floor. Thea looked up as he stepped back once again. He wasn’t advancing on her, not willingly hurting her—he was just protecting the entrance. And she had to get through that damned door.

Thea was exhausted. Her limbs trembled as she stood, hatred raging through her at his strength, his calm demeanor, the way her attacks seemed to have no effect on him at all. It wasn’t fair that she couldn’t even push him back, that all her strength wasn’t enough. In the end, she wasn’t strong enough to beat him. Just as Natalie hadn’t been strong enough.

Thea opened her eyes, rage swimming in front of them. Natalie. She let the sound of her cousin’s name ring through her head like the beat of a persistent drum, one that pushed out of her wounded heart. One more time, Thea told herself. I have in myself one more try. She closed her eyes. You’re not strong, but you are fast, she told herself. Now go!

Thea sprinted toward the boy. He put his hands out in front of him in a defensive crouch, but at the last moment, she faked to the right. He lunged to match her movement, but he wasn’t expecting her to then throw herself violently left, back toward his body. They collided in a violent tangle. Using her momentum, she flung herself toward the ornate doorknob, shaped like a beehive. Her fingers closed around it just as his arms wrapped around her waist. The door pushed open, and Thea let go of the knob and fell to the floor in front of it. She flinched and waited to be dragged backward, but nothing came. The arms around her waist loosened. Thea rolled over, the door open in front of her head. The boy in white linen got up, dusted off his pants, and stalked out the door she had come in from.

Thea slowly, painfully, climbed to her feet. Her back ached, her mouth was still numb and salty, and her breaths were so sharp they cut into her ribs. Still, she limped through the door, hoping that whatever was on the other side was worth leaving a part of herself behind.

Three

Upon stepping inside, Thea found herself in a circular room with a gold-domed ceiling. Strung across the circular walls were thick pieces of black ribbon. Attached to each ribbon, hundreds of black-and-white pictures were held by a single clothespin. Thea walked forward, her eyes tracing over the faces before her: women from their early teens well into later age. She limped forward another step, wiping her bloody mouth on the back of her hand.

In the center of the room stood an easel next to a single brown leather wingback chair. A black-and-white photograph was clipped to the top of the easel, and even before she reached it, Thea knew that face: She recognized the long black hair that had always made her jealous, the curls that bordered on the edge of messy. The freckles dashed across her brown skin, the radiant grin. Thea reached out and touched the picture of Natalie’s face, her personality perfectly captured in this moment. “I miss you,” she mouthed. She reached out and unclipped the picture, pressing it against her heart. Whatever this was, whoever had brought her here—this picture belonged to Thea, not to them.

From somewhere in the room came a voice. “We can give you what you want.”

Thea spun around, annoyance flitting across her face. They were playing with her grief, and she was done with it. “What is this? Enough with the games!”

The voice trilled with laughter. “This is not a game, Thea. This was an initiation.” At the distinctive click of high heels, Thea turned slowly. A stunning woman in her early thirties stood before her. Her hair was dark brown laced with shades of auburn and pulled back from her face in a tight bun. Her face was hard, with steeled brown eyes and jutting cheekbones, her lips painted a scandalous red. She wore a black dress under a tailored black coat. She stepped closer to Thea, who instinctively took a step backward and clutched Natalie’s photograph to her breast.

“Hello, Thea. I’m Nixon.” She paused, letting her fingers trace Thea’s shoulder. “I know you’re curious why you’re here. Your cousin Natalie Fisher was murdered, is that correct?”

Thea nodded, unable to speak, as the word murdered ripped her apart.

“And there wasn’t enough evidence to arrest her murderer, is that also correct?”

“Yes.” It was too much, thinking about the thing that she never allowed to cross her mind.

“What if I told you that there was a way to get justice for Natalie? A way to make him pay f

or his unspeakable crime?”

Thea raised an eyebrow. “Are you talking about the police?”

“I’m talking about justice. Sometimes the two aren’t the same,” Nixon answered.

Thea met her gaze. “I’m listening.”

“You are currently standing in the atrium inside Mademoiselle Corday, a very old Victorian house that happens to be owned by a quiet organization. Do you know anything about Mademoiselle Corday?”

Thea shook her head.

“Not in your history classes? Nothing?” The woman let out an irritated sigh. “Roosevelt High School, churning out tomorrow’s leaders today. Anyway, history knows her as Charlotte Corday. She murdered Jean-Paul Marat, who was part of a bloody arm of the French Revolution. She stabbed him to death in his bathroom, and in 1793 she was executed by guillotine. It earned her the nickname l’ange de l’assassinat, which means the Angel of Assassination.”

Thea stepped backward. “You’re assassins.”

Nixon smiled condescendingly, as if that was the most ridiculous thing she had ever heard. “Assassins—oh God, no. You won’t be killing anyone anytime soon. What we do is administer justice, true justice, through our organization: the Black Coats.”

The Black Coats. Thea blinked, remembering the BC on the envelope that had made its way to her in pottery class. “The Black Coats. You’re a—”

“We’re in the business of righting the wrongs done to women.” Nixon began circling her like a wolf. “Thea, aren’t you tired of being afraid in your everyday life, of not walking home alone after dark, of locking your doors, of making sure that your shorts aren’t too short lest you attract some unwanted attention? The Black Coats believe we are called to tip the scales, to restore justice. It is one small step toward restoring the world to a kinder, gentler place for our sisters. A place that doesn’t take the murder of a cousin lying down.”

The Black Coats

The Black Coats Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas

Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas Elly in Love (The Elly Series)

Elly in Love (The Elly Series) Queen of Hearts: Volume Two: The Wonder

Queen of Hearts: Volume Two: The Wonder Elly In Bloom

Elly In Bloom Queen of Hearts (The Crown)

Queen of Hearts (The Crown) Wendy Darling

Wendy Darling War of the Cards

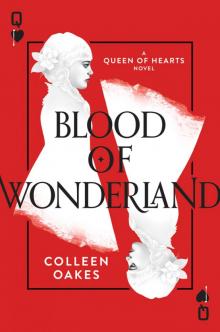

War of the Cards Blood of Wonderland

Blood of Wonderland